Roar

written by: Noel Marshall, additional script material by Ted Cassidy

produced by: Noel Marshall, Tippi Hedren, Robert E. Gottschalk

directed by: Noel Marshall

rating: PG

runtime: 102 min.

U.S. release date: April 15, 2015

"It's just like life, you get the funny with the tragic."

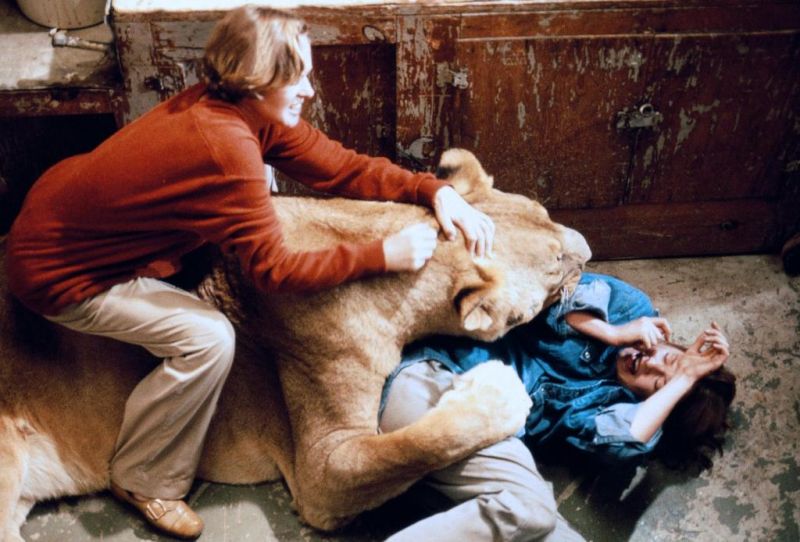

The tagline for the newly remastered re-release of Noel Marshall's forgotten 1981 film Roar reads, "There's never been a film like ROAR - and there never will be again!" This isn't hyperbole, this is 100% honest-to-goodness truth in advertising. Roar is more than an oddity, it is a literal journey into the mouth of madness; a film that took nearly a dozen years to get to the screen and saw more than seventy members of the cast and crew suffer injuries during that time period. This is a singular film, the kind of film that simply should not exist, and yet it does, and it is spectacular.

Make no mistake, this is a bad film. It's poorly made, almost out of necessity, the script is beyond hamfisted, and Marshall cast himself in the leading role despite having exactly zero credits as an actor before or since. All of this was out of necessity, you see, as Roar was something of a passion project for Marshall and his then wife Tippi Hedren. As wild animal conservationists and owners of a wildlife preservation in California dubbed Shambala, Hedren and Marshall got the bright idea to make a film that would show the world that big cats like lions, tigers, leopards, panthers, cheetahs, and the like were under constant threat of extinction due to big game hunting in Africa. A noble endeavor, to be sure, but the way they decided to go about all of this sounds more like a suicide mission than the plot of a film.

You see, in Shambala, Marshall and his two sons from a previous marriage lived with Hedren and her daughter, Melanie Griffith, in a home they shared with these various animals. Marshall was filthy rich thanks to the money he made producing The Exorcist, so they decided it would be a great idea to turn their lives into a narrative that would weave in those crucial messages against poaching. What followed would be a descent into hell, the kind of film that combines the notoriously troubled productions of Apocalypse Now and Fitzcarraldo, and then throws in ferocious animals interacting with humans for good measure.

The film does not work without this knowledge, however, which is its fatal flaw. It's no wonder audiences in 1981 greeted the film with a collective shrug, because without that knowledge, it's just a poorly constructed film with a lead actor who shouts all of his dialogue. He's also prone to monologuing, at length, about the harmony between animals and people literal feet from bloody confrontations between the big cats. The original songs by Robert Hawk recall Dan Fogelberg at his schmaltziest, and Terence P. Minogue's score is comprised almost exclusively of an unrelenting drum beat meant, I presume, to mimic the terror-induced racing pulses of the cast and crew. In its best moments, it looks like a low rent nature documentary, and at its worst, looks like a half-assed experiment gone horribly awry.

The plot, if one is so bold as to declare that the film even has one, is as simple as simple gets. Marshall plays Hank, a scientist or doctor—it's never really made clear—who lives on a jungle preserve in Africa among over a hundred large cats. A meddling bureaucracy of some sort disapproves of his methods and aims to shut his operation down. As Hank attempts to quell this tide of unrest, his wife (Hedren) and three children (Griffith and Marshall's sons John & Jerry) arrive for a visit, but they arrive when Hank is away from the sanctuary. As his family fights for survival at the compound, a pair of poachers who met the wrong end of several tigers earlier in the film, are making their way through Hank's property and gunning down any animals they encounter. Don't worry, text at the end of the film assures us that all of these lions are simply pretending to be killed, though I can't imagine any level headed representative of the American Humane Society hanging out on set long enough to verify such a claim.

Bearing all of this in mind, the film has no reason to work and yet it does, if only as a curiosity. There are moments of such singular peculiarity that they take on an almost endearing sweetness. For example, as Marshall is shooing lions out of his home, one lion named Gary, who appears to be wounded, doesn't vacate the home with everyone else. He and Marshall then have a shared dialogue in which Marshall asks Gary what's wrong and Gary responds with perfectly timed guttural responses. It's not unlike Han Solo and Chewbacca having a conversation in Star Wars, but where the threat of Chewbacca actually pulling Han's arms out of their sockets is frighteningly real. It allows the audience to see how Marshall could have possibly seen these animals as oversized kitty cats, but his still fresh wounds also serve as damning evidence that he was only fooling himself.

If you are a lover of all things bizarre in cinema, this is absolutely essential viewing. I would implore you to first read Alamo Drafthouse CEO Tim League's essay about the film's production, and lay eyes on the photo of cinematographer Jan DeBont's massive head wound. This is not a film for casual bad film fans as it's pretty next level stuff, and though no one was killed, you will see how precipitously close a film can become to being a snuff film without actually crossing that line. It makes a brilliant companion piece to Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man, which is essentially the worst case scenario version of this film. If you are a lover of bad films, and want to see something that is unlike anything else that's ever been made, this is essential viewing. Bear in mind that my final score is reflective of the fact that I do consider myself to be a bad movie connoisseur, and feel free to subtract at least two stars if you're not. For those of who crave that thrill of a car crash's aftermath, however, you can't get much closer to the real thing than with Roar.

GO Rating: 4/5